Outcomes

WHAT WE’VE LEARNED

Publications

Wall has published four articles discussing the outcomes of this project. Three are available online; one is available only in print.

The essay in print is here:

“Virtual Paul’s Cross: The Experience of Public Preaching after the Reformation,” in Paul’s Cross and the Culture of Persuasion in England, 1520–1640, ed. Torrance Kirby and P.G. Stanwood (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2014), pp. 61 – 92.

The three available online are the following:

“Immersing Oneself in the Past: The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project.” In The Immersive Scholar (2018). https://www.immersivescholar.org/news/pauls-cross-NCSU.

“Recovering Lost Acoustic Spaces: St. Paul’s Cathedral and Paul’s Churchyard in 1622.” In Digital Studies/Le Champ Numérique (Proceedings of the SDH-SEMI 2012 Conference). (http://www.digitalstudies.org/ojs/index.php/digital_studies/article/view/251/310)

and

“Transforming the Object of our Study: The Early Modern Sermon and the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project,” in the Spring 2014 issue of the Journal of Digital Humanities (http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/3-1/transforming-the-object-of-our-study-by-john-n-wall/).

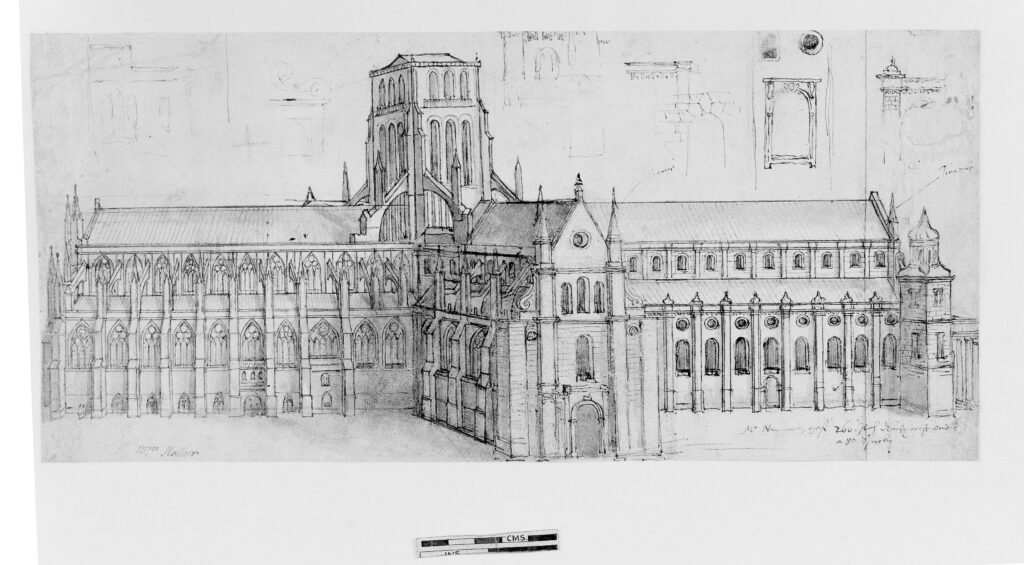

In addition, this Project demonstrates the value of using digital modeling technology in organizing, assessing, and visualizing the relationships among a wide range of information regarding lost structures, spaces, and the relationships among them. This Project shows how we can integrate information provided by a large number of sources — in this case, visual depictions of St Paul’s Cathedral and its immediate environs — together with accurate measurements of foundations, elevations, and spatial configurations of objects.

The availability of quantitative information such as measurements, both historic and modern, of foundations, distances, and heights has enabled the reconstruction of buildings and the spaces that connect them in highly accurate ways. This information provides a perspective from which to evaluate visual data from the past that is often presented on the basis of understandings of perspective, scale, and accuracy of presentation different from our own.

This Project makes clear, for example, how images like John Gipkin’s painting of Paul’s Cross depict people and objects according to rules of social order and the desire to show what is important to the painter rather than according to the rules of photorealistic depiction or naturalistic perspective.

The Project also demonstrates how site specific information such as data about weather, climate, and environmental conditions can be integrated into architectural models of historic spaces. It also demonstrates the limits on digital depiction to certain kinds of sensory perception and not to others. Simply put, we were able to model the look and sound, but not the smell.

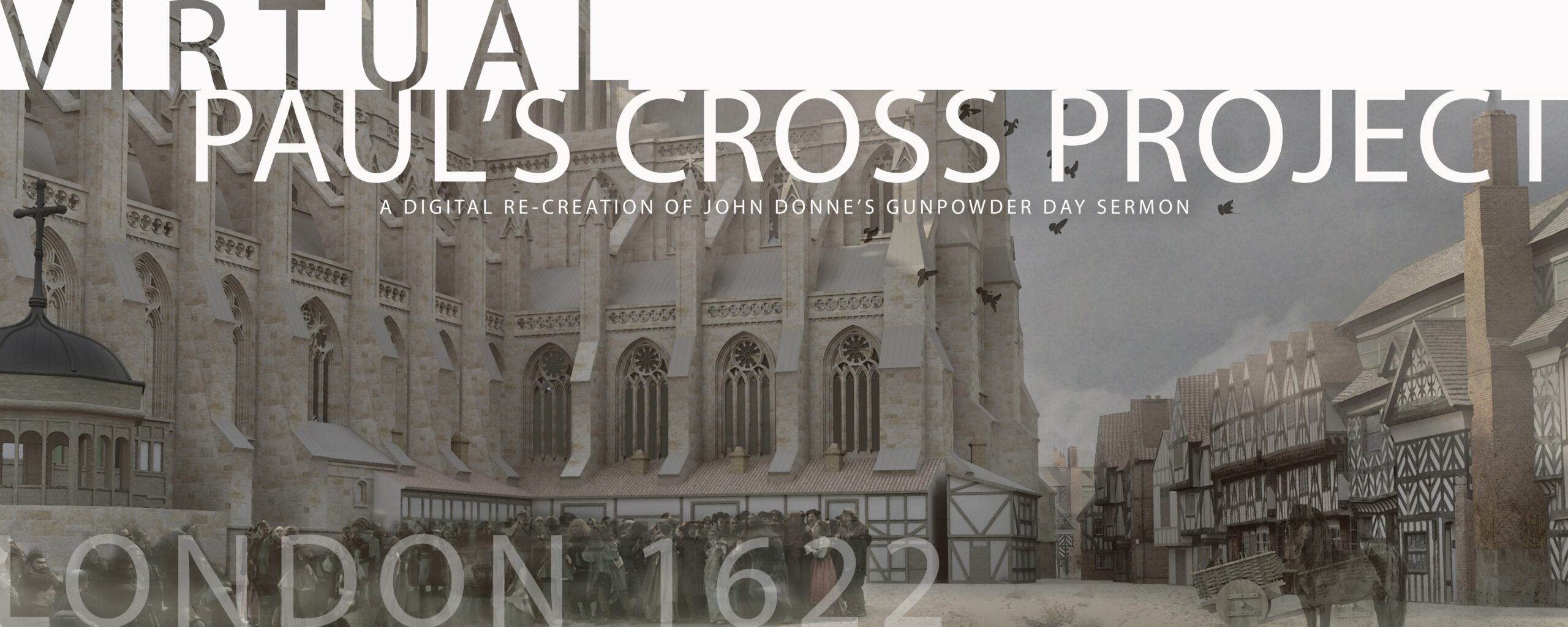

Figure 2: Paul’s Churchyard through Paul’s Gate. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

The acoustic model has also demonstrated the capacity of such models to inform us about the quality of sound in lost spaces and thus to evaluate the challenges and opportunities faced by people trying to be heard in those spaces. It is one thing to know, in theory, that Donne faced challenges in being heard when preaching in Paul’s Churchyard, and quite another thing to know what kinds of challenges he faced and how serious those challenges actually were.

The acoustic model also allows us to explore and assess contemporary descriptions of preaching styles. We are told that Donne was witty, eloquent, visionary, communicative of feelings. We can experience these and other possible modes of address, section by section, as we work through these sermons.

The acoustic model also allows us to experience the early modern sermon as a performance that unfolds in a specific space and in real time. We can experience it as a moment-by-moment event, in relationship to the space of its delivery, the markers of time as it passes, and the unfolding of possible congregational responses.

The sermon text therefore becomes one side of an interactive performance, which at least occasionally allows us to glimpse the other side, the character and quality of congregational response.

Figure 3: Paul’s Cross from the Sermon House. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

The process of sermon-making has also become more visible. We have become aware of the implications of the fact that preachers did not read their sermons but worked from memory and from notes, and from the challenges of the congregation and the physical realities of place, time and occasion.

Thus the records — either manuscripts or printed copies — of early modern sermons are after-the-fact reconstructions of what was actually said on these occasions. We can glimpse the nature of the actual event, but through our ability to note traces of the occasion through the written or printed text that came after it.

We are also more aware of how early modern preachers were working within a tradition of expectation about how occasions of public worship would proceed, in terms of what was said, how familiar it would be, and who would do what sorts of things, and in what style, and in what manner.

These expectations were shaped in part by the tradition of worship guided and enabled by use of the Book of Common Prayer but also by factors such as the culture of public theater and the demands for preachers to entertain as well as inspire as they preached their sermons.

We can therefore come to know more fully how the Paul’s Cross sermon was able to shape and inform religious discourse in the early modern period, and to appreciate more fully the connections between this form of communication and other forms, most notably the form of print, marketed in the Booksellers’ shops that surrounded the Cross Yard.

We can also come to appreciate Bruce Reed’s argument in The Dynamics of Religion that religious faith in practice is less about assent to verbal formulas like the Creeds than it is a disposition, a physical as well as intellectual orientation, that is formed through participation in a set of practices that establishes and supports an understanding of self in terms of social networks and shared participation in the formation of relationships.

The Paul’s Cross sermon as public event — as a regularly scheduled occasion for a public gathering — surely had its aspects of carnival, its reward for seeing and being seen. Tiffany Stern has spoken of the public sermon as an occasion to take notes and hence to enrich one’s understanding of and commitment to (or reaction against) the Church of England, or to particular spokesmen for it. But, she notes, it was also an occasion to display one’s faith, to perform the role of good Christian, precisely by taking notes, by doing things that one’s neighbors would interpret about one’s faith, according to social and cultural norms of the day.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, because it features a sermon that was intended for Paul’s Cross but instead was “Preached in the Church . . . by reason of the weather,” also reminds us that attendance at these events was often a personal challenge, not just an occasion for communal display. Matthew Smith has recently argued (in private correspondence) that there was an element of “physical and mental strain (what Donne calls “pain”) just as much as didactic comprehension that comprised the kind of faith produced by sermongoing.”

In Smith’s view, “one’s faith becomes social, acoustically diffuse, distracted, but also mentally focused and physically strained.” Smith notes, developing Stern’s argument, that “Sermongoing faith was also . . . shaped by the writing and mnemonic technologies incited by such a sermongoing experience as you capture on your site: table books, short-hand writing, technologies of erasure, portability, and the skill of reciting the ‘main points’ to one’s family and perhaps servants.”

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project supports such lines of inquiry by making the Paul’s Cross sermon the subject of reflection precisely as a situated experience, a communal and participatory experience, unfolding interactively in real time and in a specific place, under specific conditions of weather, season, and urban environment. I believe this work has just begun.

Recognitions

ACENTECH — our Acoustic Engineering Partners — https://www.acentech.com/project/virtual-pauls-cross/

Reviews in Digital Humanities for June 2024 (https://reviewsindh.pubpub.org/v5-n6) has a very positive review by Erin McCarthy (University of Galway).

National Endowment for the Humanities — our funding agency — https://www.neh.gov/explore/virtual-pauls-cross-project

The Spenser Review — Review by Matthew Smith — https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/spenseronline/review/volume-44/442/digital-projects/meeting-john-donne-the-virtual-pauls-cross-project/

Musical Geography Website — https://musicalgeography.org/2020/12/07/virtual-pauls-cross-project/

Early Modern Digital Review — Review of Paul’s Cross website by Brent Nelson — https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/emdr/article/view/36586/27832

Cradled in Caricature — https://cradledincaricature.com/tag/st-pauls-cross/

Coverage in the Guardian Newspaper 11 November 2013