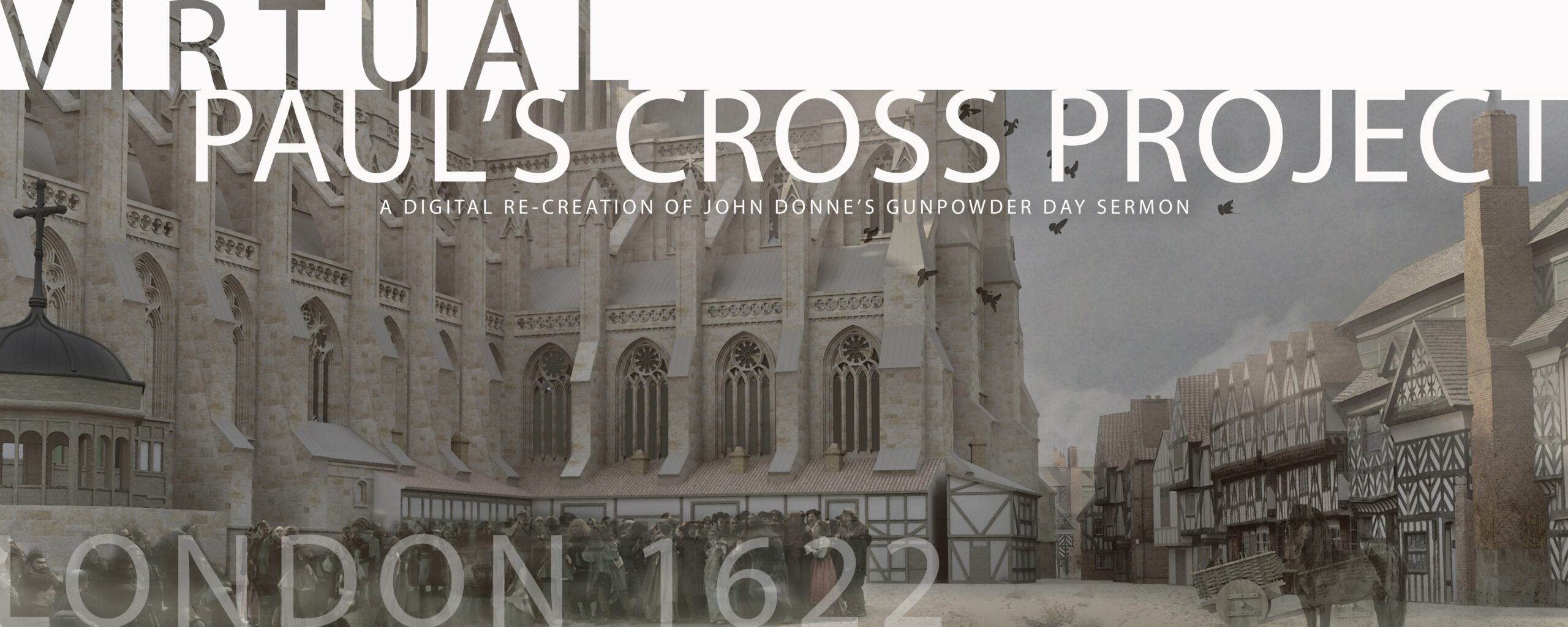

Figure 1: Paul’s Cross, from about 75 feet. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

HEARING THE AMBIENT NOISE

Included in the experience of listening to Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon are some, but certainly not all, of the kinds of ambient noise that would have provided an acoustic background to the preacher’s delivery.

We have chosen to include a selection of sounds for which Gipkin’s painting of a Paul’s Cross sermon provides documentation. These include horses, birds, and dogs.

Figure 2: Details, John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Images courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

These sounds are programmed to be heard randomly in relationship to the preacher’s delivery. There has been no effort to “script” their appearance.

There are of course other possible sources of ambient noise. The sound of water flowing in the Thames, only a few hundred yards away, might well have been audible. The sound of people — and their horses and carts — moving through the streets just on the other side of the buildings surrounding Paul’s Churchyard was certainly part of the acoustic background.

The sound emanating from Paul’s Walk — the nave of St Paul’s Cathedral, the largest enclosed space in London, notorious in this period for being so noisy that it disrupted worship in the cathedral’s Choir — may also have been audible outside the cathedral.

The Bell

The bell, on the other hand, provides a different kind of ambient acoustic experience. Thanks to Tiffany Stern’s research (2011), we know that the clock at St Paul’s Cathedral sounded the time on the quarter hour as well as on the hour.

Here, the bell ( a struck clock bell, not a swinging peal bell) sounds on the hour at 10:00, 11:00, and 12:00, as well as on the quarter hour. The extent of congruence between the rhetorical structure of Donne’s sermon and the sound of the bell has been sufficient to suggest that Donne drew on the way the clock bell structured time to organize the structure of his delivery.

The Process

The acoustic model was constructed by Ben Markham and Matt Azevedo of Acentech Incorporated, in Cambridge, MA, using the CATT-Acoustic modeling program, based on a simplified version of the visual model.

The behavior of sound in space is well-understood today. We know that sound, once made, travels at a certain speed until it bumps into something, at which point it is either absorbed, reflected, or dispersed, depending on the shape of the object it hits and the materials out of which the object is made.

Joshua Stephens, who built the visual model, revised his model for acoustic modeling purposes and supplied Ben and Matt with an account of the materials used int he construction of the original buildings.

Ben supplies us with a more detailed account of the acoustic properties of this space in his Acoustic Engineer’s Report on the next page.

The sound clips below position the hearer in Paul’s Churchyard to experience the acoustic model on its own, with the sounds of ambient noise but without the sounds of the preacher.

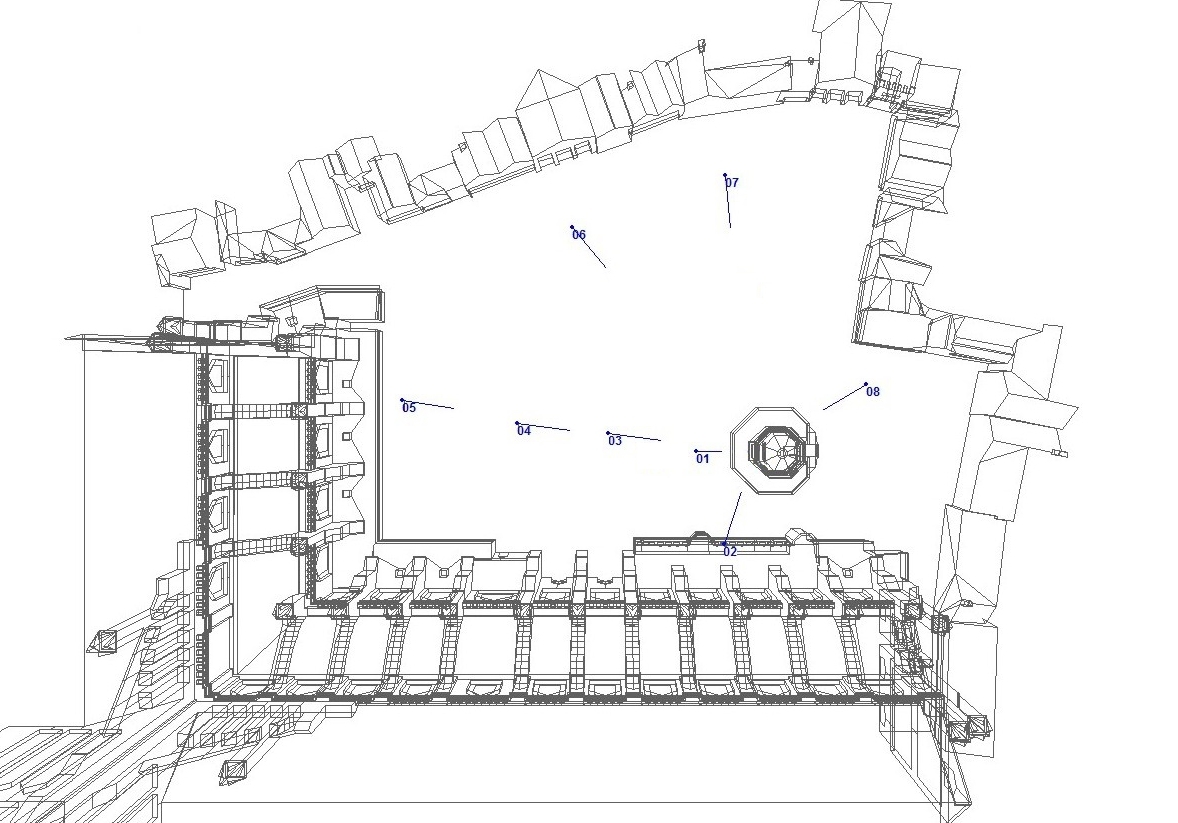

Figure 3: Wireframe Image of the Acoustic Model, Paul’s Churchyard, the Cross Yard. Wireframe from the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

Each clip positions the hearer in position 4 in the diagram above. Each sound clip lasts approximately 1 minute and a half, and provides an experience of Paul’s Churchyard as a physical space.

The first three clips locate the hearer in the middle of the space between the Paul’s Cross preaching station and the north transept of the cathedral, about 30 feet from the side of the choir.

The first of these sound clips presents the Churchyard empty of human life, except for the rider on the horse that trots through during the course of the recording. The space is given over to the dogs, the horses, and the birds visible in John Gipkin’s painting.

One might imagine oneself standing in the churchyard early in the morning, before the crowd has begun to gather for the sermon.

The second clip adds to the sounds of animal life the acoustic traces of about 250 people, essentially the number of people shown listening to a Paul’s Cross sermon in Gipkin’s painting.

Figure 4: Detail, John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

One might imagine oneself arriving to join them, perhaps about 9:30 in the morning

The third clip raises the number of listeners to about 2500, about half the size of the largest estimates of crowd size that come down to us from the post-Reformation period for a Paul’s Cross sermon.

The fourth clip moves us to the “Royal Box” in the Sermon House, against the north wall of the Choir, the Seat of Honor from which Gipkin shows us James I listening to that day’s Paul’s Cross Sermon.

Figure 5: Detail, John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

The number of auditors is again about 250, roughly the number shown in Gipkin’s painting.

Again, the crowd has gathered and is awaiting the arrival of the preacher with his entourage.

The fifth clip also places us in the Seat of Honor in the Preaching House, but this time the crowd has swelled to about 2500 people who await the arrival of the preacher.