Framework

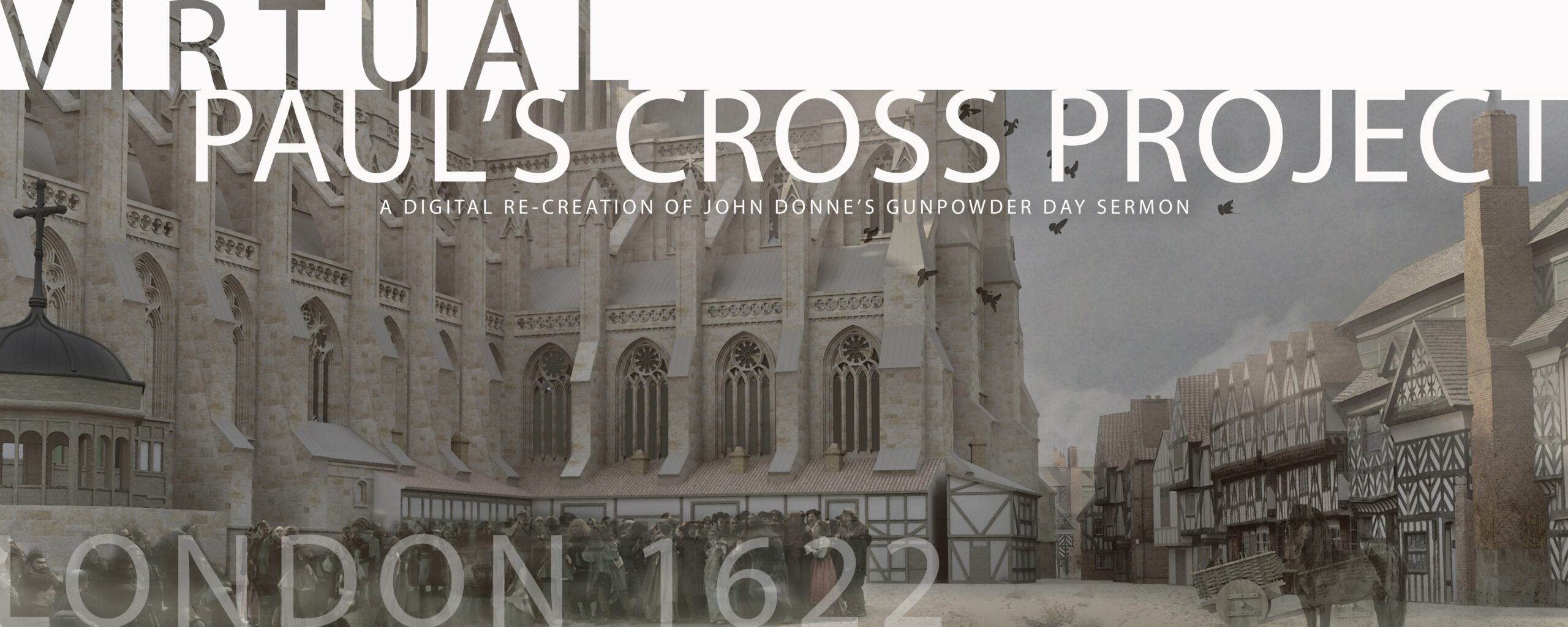

Figure 1: Paul’s Cross from 50 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Figure 1: Paul’s Cross from 50 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF SITUATED SIMULATIONS

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project provides the opportunity to experience the phenomenon of the Paul’s Cross sermon, an occasion of outdoor public preaching at Paul’s Cross in Paul’s Churchyard in early modern London, as an event unfolding in real time, in a space modeled after the space in which it was originally delivered, in the presence of a large public gathering of people, and with at least the suggestion of the conditions and circumstances in which they gathered for its original delivery.

As such, it enables us to identify and evaluate our understanding of the Paul’s Cross sermon as a social phenomenon, as an interactive occasion, as a public event. The Paul’s Cross sermons were actually composed in the process of delivery by a preacher working from notes who faced a congregation gathered in the open air and surrounded by a host of distractions, including the birds, the dogs, the horses, the bells, and each other.

While the early modern preacher had developed a capacity for working within an implicit framework of organizational structure and dramatic presentation, so the content of his delivery was logically coherent and supported by his delivery, he was chiefly interested in engaging with his congregation emotionally as sell as cognitively, emphasizing the preacher’s capacity to move as well as to teach.

His congregation came to the sermon to participate in the experience as well as to gain insight to take away with them at the end of the event. The Paul’s Cross sermon was thus a collaborative creation, a two-hours-traffic upon the Churchyard, a conversation between preacher and congregation, with its own architecture of space and time, its own distribution of roles and parts, which, if effective, no one left unchanged, unformed by the occasion.

Background

The goal of the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project is for us to experience the Paul’s Cross sermon so that we may become more fully aware of the assumptions, conventions, and conditions of its original delivery. Our process for doing this is to make available the text of one such sermon as an acoustic rather than a visual experience through a performance that aspires to simulate the original conditions of delivery as fully and as accurately as we can.

This Project does not claim to take us back in time. We of course cannot know the full details of the occasion for a Paul’s Cross sermon, either in general outlines or in date-specific particulars. We cannot know what specific preachers sounded like, or how fast or slowly they spoke, or how loudly, or how or when they gestured with their hands. We cannot know (for reasons we will explore later) what precise words they actually spoke.

We cannot know the size of the crowd assembled to hear him, or how they responded to his delivery. We cannot know the temperature, or the weather, or the timing or character of ambient sounds that competed with the preacher’s voice. The list of the unknown, and the unknowable, is infinitely long.

But not knowing everything is not the same as knowing nothing. We do know some things. Some of the things we know we know with great, even remarkable, accuracy; other things we know typically or generically, or with a greater or lesser degree of approximation.

What We Can Know Visually

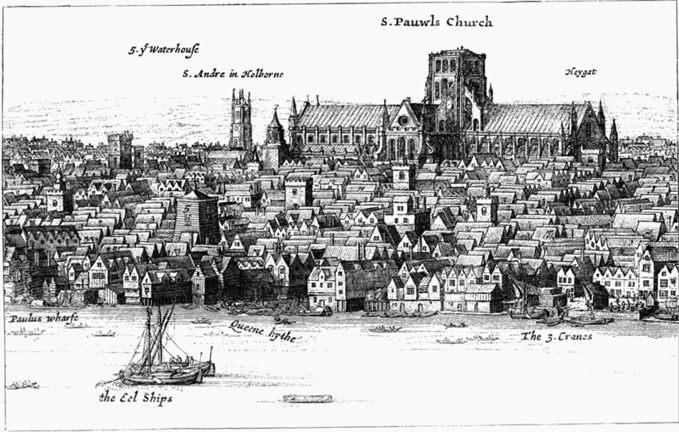

Figure 2: Detail from Wenseslaus Hollar, engraving, London, Panoramic View, Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Figure 2: Detail from Wenseslaus Hollar, engraving, London, Panoramic View, Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project provides a method for integrating and making available for inspection the archaeological and visual record of preFire St Paul’s Cathedral and its environs.

Figure 3: St Paul’s Cathedral, Detail from the Copperplate Map (1550?). Image courtesy the Museum of London.

Figure 3: St Paul’s Cathedral, Detail from the Copperplate Map (1550?). Image courtesy the Museum of London.

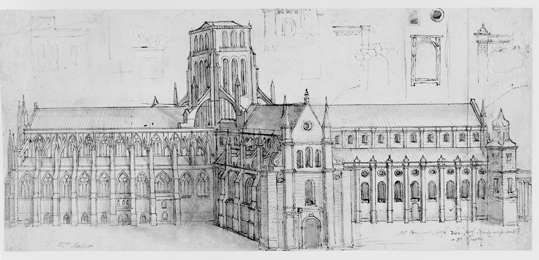

We know a great deal about what St Paul’s Cathedral looked like, thanks to the large number of drawings and engravings that survive from the 16th and 17th centuries, including images like the one, above, from the Copperplate Map of the mid-sixteenth century, but especially the program of drawings and engravings by Wenseslas Hollar that were commissioned by William Dugdale for his History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658).

Figure 4: Wenseslaus Hollar, drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side (1650’s). Image courtesy Sotheby’s, London.

Figure 4: Wenseslaus Hollar, drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side (1650’s). Image courtesy Sotheby’s, London.

We know the general appearance and approximate scale of the Paul’s Cross preaching station from 16th and 17th century engravings and especially from John Gipkin’s painting of Bishop John King preaching before James I at Paul’s Cross in 1616.

Figure 5: John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Figure 5: John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

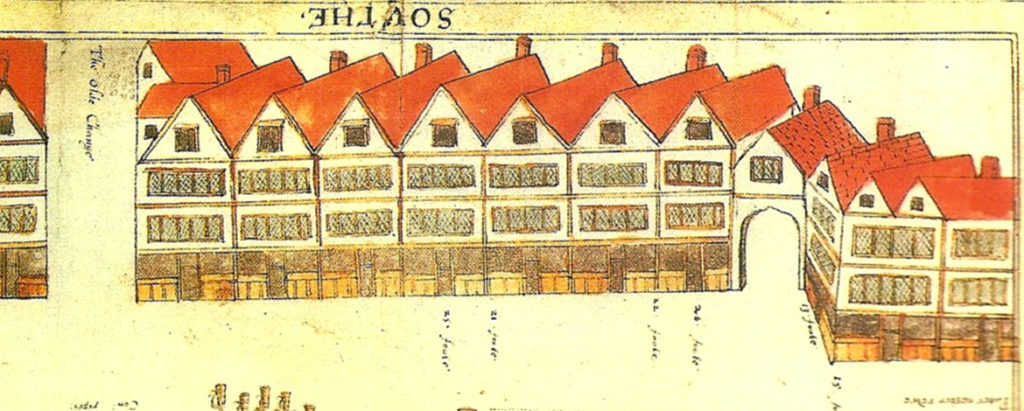

We know approximately what the buildings surrounding Paul’s Churchyard looked like because buildings of a similar function and scale survive in English cathedral towns and urban areas today.

Figure 6: Drawing, London, Intersection of Pater Noster Row and Old Change (1585). British Museum ms. BM Crace 1880-11-13-3516. Image courtesy British Museum.

Figure 6: Drawing, London, Intersection of Pater Noster Row and Old Change (1585). British Museum ms. BM Crace 1880-11-13-3516. Image courtesy British Museum.

We know, on the other hand, some things about Paul’s Churchyard and its surrounding structures with a high degree of accuracy. One is the dimensions of the foundation of the pre-Fire cathedral which remains in the ground in London, and have recently been measured. (Schofield 2011).

Figure 7: St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1640. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011).

Figure 7: St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1640. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011).

We know the dimensions of the interior spaces of St Paul’s Cathedral because Christopher Wren surveyed the dimensions of the building in the early 1660’s; his measurements survive in a drawing he submitted to the Crown in 1665 to illustrate a proposal for repairing the fabric of the cathedral after the neglect of the Commonwealth period.

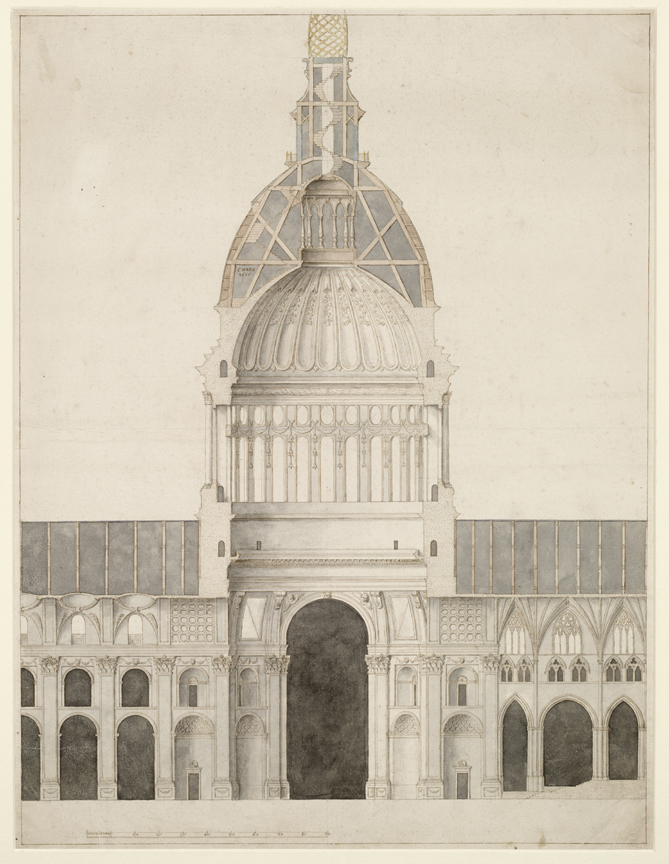

Figure 8: Christopher Wren, Scale Drawing of pre-Fire St Paul’s Showing Proposed Dome (1662). Image courtesy Warden and Fellows, All Souls College, Oxford.

Figure 8: Christopher Wren, Scale Drawing of pre-Fire St Paul’s Showing Proposed Dome (1662). Image courtesy Warden and Fellows, All Souls College, Oxford.

We know the size of the base of the Paul’s Cross preaching station because it, too, remains in the ground in Paul’s Churchyard and was surveyed in the late 19th century (Penrose 1870).

We know the size and basic configuration of the houses that surrounded Paul’s Churchyard because they were among the buildings surveyed after the Great Fire of London by Robert Hooke, Peter Mills, and John Oliver; the records of Mills’ and Oliver’s surveys survive and have been published by the London Topographical Society (1962-67).

The visual model we have made integrates data from surveys of existing structures together with the surviving visual record of the cathedral and its environs has enabled us to create a highly accurate, substantially correct visual model of Paul’s Cross and Paul’s Churchyard in the 1620’s.

What We Can know Acoustically

The visual model of Paul’s Churchyard makes possible recovery of the acoustic properties, and therefore the experience of sound, in these lost spaces.

The visual model has been the basis for the creation of a highly accurate acoustic model of this space, incorporating reverberation (greater when heard from the Sermon house than from the ground level in front of the preaching station) and the sounds of ambient noise from the birds, dogs, horses, and people whose presence is witnessed to by John Gipkin’s painting.

Figure 9: Detail from John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Figure 9: Detail from John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

When we consider the sounds of the early modern sermon, there is, again, much that we do not and cannot know.

But, again, there are things we can know. We know, for example, that the manuscript for Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon for November 5th, 1622 — a memorial reconstruction of his sermon written out by a scribe soon afterwards for King James and containing correction sin Donne’s own handwriting — provides us with a text that is as close to what Donne actually said during that sermon as we are likely to get for any Paul’s Cross sermon by any of the many preachers who held forth in Paul’s Churchyard.

We also know that Donne was a Londoner, and so the script of this sermon prepared by the linguist David Crystal in early modern London dialect is as close to the sound of Donne’s voice as we are likely to get.

For more on the background for original pronunciation of early modern London speech, go here for a discussion, including a video by David Crystal and his son Ben Crystal. Here, David explains how he has developed his understanding of early modern London English pronunciation. Ben gives us examples of speeches by Shakespeare in both current English pronunciation and early modern pronunciation.

Ben Crystal is, of course, the actor who performs John Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon for November 5th, 1622 for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project.

We cannot hear Donne’s voice, but we do know from the text of his sermons that he could convey information and concepts in a clear and well-organized manner. We also know from contemporary accounts of his preaching style that he could engage his congregations strongly, and in a number of ways. He could be entertaining, witty, charming; he could be emotionally moving, sometimes elevating them with a sense of holy things, sometimes bringing them to tears. But we are also told that he preached with a sense of decorum, not, we are told, “like our Sons of Zeal, who, to reform /Their hearers, fiercely at the pulpit storm.”

We also know that Donne’s congregations — especially those at Paul’s Cross — could be lively, bringing with them their own agendas. While Arnold Hunt notes (Hunt 2012) that diligent sermon-goers often spent their time taking notes of the day’s preaching for consultation during the week, Donne himself, in a sermon preached at Paul’s Cross, affirms a more active, more vocal, participation, noting that sometimes congregations “answer the Preacher . . . with these vocall acclamations, Sir, we will, Sir, we will not” [and with] periodicall murmurings, and noises [which] swallow up one quarter of his houre.” (Donne Sermons, X, 133-34)

Figure 10: Paul’s Cross from 75 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Figure 10: Paul’s Cross from 75 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

For all these reasons, we have chosen Donne’s Paul’s Cross sermon for November 5th, 1622 as the centerpiece of this situated simulation. The actor Ben Crystal has sought to embody all these tones and modes of delivery at appropriate moments in his performance of Donne’s sermon.

We of course cannot know specifically how Donne’s congregation on the morning of November 5th, 1622, but we have been able to suggest the presence in our virtual Paul’s Cross sermon of an active and responsive congregation by linking the energy of Ben’s delivery to the sound of the congregation. Their responsiveness serves as a reminder of their presence, their attention to the unfolding of the sermon, and their participation in an interactive occasion.

Changing Our Perspective

This project does not pretend to provide a literal recreation of a lost event. Its capacity for imagining past conditions is limited. It is highly accurate in some details while in others it is at best a representative approximation. The details of early 17th century experience it models are limited; we have not, for example, tried to model the stench of London life.

It does seek, however, to change our perspective on the events it models, bringing up new questions about the early modern sermon even as it tries to disturb settled assumptions.

Our experience of early modern preaching today is, of course, mostly a private experience, one customarily taking place in the office of a historian or scholar of early modern literature or culture, or, perhaps in a research library or scholarly archive. Such spaces are quiet, enclosed, sparsely populated, well-lit and climate controlled.

Our reading experience supports our understanding of the text of an early modern sermon as essentially a theological essay concerned chiefly with the logical and orderly presentation and defense of a set of ideas that add up to a coherent argument in support of a particular cognitive position.

Figure 11: Paul’s Cross from 25 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Figure 11: Paul’s Cross from 25 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Even when we consider these texts as scripts for delivery, we consider them as public lectures, and imagine their being delivered to a quiet and attentive audience in a distraction-free hall where those attending are able to hear every word.

Audiences in attendance at recent public deliveries of Donne’s sermons by such notable academics as Oxford’s Peter McCullough and Toronto’s Paul Stanwood are remarkably well-behaved, demonstrating their highly-developed skills as passive listeners. They are far from the audiences Donne describes as responding so energetically and at length to his sermons that they delay the course of the preacher “for up to a quarter of an hour.”

The early modern preacher, and especially one working outdoors, in the elements, in the midst of cosmopolitan and urbane and rapidly growing London, sought as Sir Philip Sidney put it in defense of didactic poetry, to engage his audience, to teach, delight, and move his audience, presenting the content of his sermon delightfully, so that they would be moved to “take that goodness in hand, which otherwise they would fly as from a stranger.”

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project asks us to view the Paul’s Cross sermon as an event unfolding in real time, in a space shaped much like a public theater, in the presence of a large public gathering of people. who came to enjoy a public occasion even while seeking spiritual enrichment and theological education. Donne and his contemporaries cautioned their listeners to avoid the pleasures of the theater even as they helped organize and participated in events that were in their own way highly theatrical, drawing on conventions and expectations of early modern culture that Paul’s Churchyard and the public theaters held in common.